Jürgen Engelhardt (1980)

A Few Comments about the Aesthetics of GDR-Jazz

I Jazz instead of/or Folk Music

"I think that in our country one cannot simply sit down and copy what American musicians have developed. One could do so but it would have no real effect except perhaps to bring in money. It is important to recall one's own traditions which one carries around like a rucksack. I grew up in an area where I heard many folk songs but not until the beginning of the 70s did I consciously become involved in folk music."

(Ulrich Gumpert) 1)

An inherent folk music did not exist for American jazz in post-war Western Germany, known briefly as German Jazz. Jazz instead of/or folk music was a means of public repression, a mutual substitute for collective consciousness. To swing was to breathe a sigh of relief. Only in education was there a continued and unceasing occupation with folk music. One knew that German singers had no love for the interjected question.

In jazz one took hold of folk music only sporadically, in scattered instances. When jazz did take hold of folk music, it did so sporadically and only in those areas not yet occupied by Fascist ideology:

"In this context we are speaking not only of Asia. The subject here is the opening of musical culture and musical areas which did not previously seem to exist for jazz. To these areas belong inherent traditions in Germany with which the German musician has possessed and still possesses an uneasy relationship from the very beginning. (….) In 1964 Albert Mangelsdorff and his musicians were asked again and again why they had no numbers on their program from Germany's musical past. We agreed that what was normally regarded in Germany as folk music could not be used. This is why, while preparing our Asian tour I delved back into the grand old eras of German folk music, back into the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries when many of our songs were still modal (similar to contemporary jazz and similar to the Asian themes chosen by Albert)." 2)

Folk music as something exotic. Alienation in your own country.

Folk music as plebeian music, as a naive and aesthetically complex compensation and as a social utopian design lies devastated. This is an important point when we observe jazz from the GDR; for a peculiar music socialization is always listening in.

Only recently, by the way, have the (young) folk once more approached their music. The neutralizing term "folk" is available to them. One plays folk music.

In the GDR, it was reversed.

British Field Marshall Montgomery had said: "If we cannot conquer the Communist Earth with weapons, we will succeed with the jazz trumpet" 3), and the GDR confirmed his statement:

"Because the Fascist regime had denounced and suppressed jazz and labelled it 'degenerate' and 'Nigger Music', it came to Germany after the war in the first instance and exclusively as American music in the forms which then predominated: namely Bebop, Hardbop, Cool Jazz. These forms were consumed and reproduced by the native German musician exactly as they were delivered to him. Since at the end of the 40s and the beginning of the fifties jazz still maintained a certain assigned ideological function in the cultural political influence of the western occupying powers, it was at that time largely rejected here." 4)

The GDR spurs on the folk and the folk music without for the most part, "folksiness". Wolfgang Steinitz received the best edition award for his work "Six Centuries of German Folk Songs with Democratic Character". Hanns Eisler wrote "New German Folks Songs".

II The Folk Song as Backbone

Aesthetic Potential

The folk song was simultaneously the subject source and catalyst for contemporary GDR jazz at the beginning of the 70s and provided a means of extracting GDR jazz from the aesthetic diction of the American prototype in an independent and authentic way. Rejection in the west of swing and beat could hardly be taken over fully. One of the rules of student protest, that of crisis emotion and an appropriate letting off of steam in complete sound spectrum, was adopted because there was aesthetically little to reject. Naturally, studies in sound were a, so played, but an argument with inherent tradition lay closer: "Jazz tradition, for me, methodically considered, is European tradition with an important statement." 5), says Gumpert and indeed the folk song has aesthetic possibilities which are comparable to the Blues in the excitement of its contents and its historical function. As with the Blues it (the folk song) devours improvisation with substance, gives it form and structure, references for a developing music language without dissolving within it. It causes change without itself being changed. As "a backbone" its makes free improvisation possible, which then fees itself from the traditions brought with it, and comes to its own socially relevant aesthetic identity. The difference between folk song and Blues is only that the folk song always stood in opposition to plebeian utopia and upper class abuse. It is, in the same way, appropriate to throw off deleterious "games" and establish new measures of aesthetics. In place of the folk song which is only quoted and only used, which expresses quite different social and historical conditions, further development can bring forth a self-produced national characteristic. For, without a doubt, it is my impression after hearing GDR jazz for the first time that the jazz of Gumpert, Sommer, Petrowsky is more nationalistic, more realistic, more educational, more pleasurable than most of the New Jazz here at home which still strenuously divides itself between free improvisation and the comic.

The bewildering thing is that the various musical sources which make up GDR jazz have led, in a relatively short time, to a musical language which is concise, though understandable, unifying though complex and contradictory: "I believe that many elements are interwoven: that which is really felt and the traditional, used with a touch of ironic perspectives. I like to speak of concrete music, not in the sense of musique concrete but in the sense of directness, direct appeal to surroundings and audience. When something is formulated in a direct manner there is a greater chance that something will remain with the public. In this regard a few things can be learned from Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht." 6)

And not only from them. With ideologically critical delicacy, aesthetic know-how and knowledge of instrumental technique came together:

- aesthetic emancipation which western Free Jazz has developed while going off the beaten track and merging (Burde) with the musical avant-garde (new structures in form, open work concepts, sound surfaces, tone colourings and the equal right of noise, a new structured feeling for time).

- folk music

- imposing European music and artificial European state music which it then approaches

- American jazz with its modern strongly marked style

- methods of montage, parody, alienation as they were developed (in the20s) in the socially involved, anti-romantic art which itself was a response to the First World War.

Two of these aspects should be investigated more closely: The folk song as aesthetic and subject basis, as well as parody and alienation. The following records were used in the analytical observation:

Recordings used:

Jazz-Werkstatt-Orchester: Aus teutschen Landen, Suite nach Motiven deutscher Volkslieder; Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht - Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen - Der Maie, der Maie - Es saß ein schneeweiß Vögelein - Kommt ihr G'spielen. Rec.: 4. 9. 1972 ,,Jazz in der Kammer" Nr.48 Berlin. Amiga Jazz - 55 549

Ernst-Ludwig Petrowsky Quartet: Just for fun; Zugabe - Just for Fun - Bohnsdorf - Tango I - Tango II - Ohne mich - Sonatta. Rec.: 29. 4. 1973 Rundfunk der DDR, Berlin. FMP 0140

Gumpert-Sommer-Duo plus Manfred Hering: The Old Song; Ein Holz für Angelika - Wiesenlied - Sommers faife - Wo bleibt mein schwarzer Krauser - dipp-dapp - The Old Song - A New Song - s'Inlett - Duo - s'InIett - Aus teutschen Landen - Juschis Murmeln. Rec.: 17./18. 7. 1973 Rundfunk der DDR, Berlin. FMP 0170

Synopsis: Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil; Krisis eines Krokodils - Zweisam - Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil - Petting zu „Take IV" - Take IV - Mehr aus teutschen Landen a) Saß ein schneeweiß Vögelein, b) Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen. Rec.: 5./6. 3. 1974 Rundfunk der DDR, Berlin. FMP 0240

Gumpert-Sommer-Duo: …jetzt geht's Kloß; Kloß 1 - Kloß 2. Rec.: 30. 1. 1978 „Jazz in der Kammer", Nr. 102 Berlin. FMP 0620

Ulrich Gumpert Workshop Band: Unter anderem: N'Tango für Gitti; Marsch, Marsch - Königskindisch - Aus Baby' s Wunderhorn - N'Tango für Gitti - Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil - Jubilee Suite. Rec.: 14. 7. 1978 Rundfunk der DDR, Berlin. FMP 0600

Ulrich Gumpert Workshop Band: Echos von Karolinenhof; Hahnenkopf - Septettfragment - Blaue Blusen Blues - Echos von Karolinenhof - Hilferuf einer Schnecke. Rec.: 1./2./4. 3. 1979 Workshop Freie Musik, Berlin. FMP 0710

Gumpert-Sommer-Duo: Versäumnisse. Rec.: Workshop Freie Musik 1979, Berlin. FMP 0740

Brötzmann/Van Hove/Bennink: Einheitsfrontlied. FMP S 3

Heiner Goebbels/Alfred Harth: Hommage/Vier Fäuste für Hanns Eisler. SAJ-08

Material for Improvisation

Concrete intercourse with folk music is the strafing point of new GDR jazz. That it, folk music, is not the goal but rather a stage of critical and aesthetic argument is shown in the chronology of the recorded material before us: as years pass, more and more of the original folk music is lost until merely a hint of the original phrase is left.

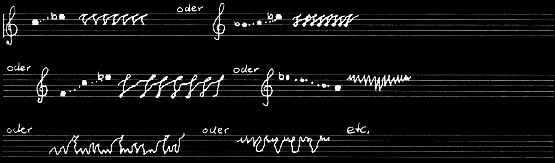

Two things may have attracted Gumpert to the folk song; use of varying tonal systems (modality vs major-minor) and rhythmic variety.

1. Tonal tensions

An important principal in the development of American jazz, proceeding from the Blues cadence and European dance forms, is the constant widening of harmonic relationships. Here, the interplay between ambiguous Blue notes (which themselves consist of a mixture of African and European tonal systems) and the improvised explanation of a harmonic intertwine reveals the constantly changing impulse of new musical forms. In his works on the folk song "Aus teutschen Landen" Gumpert uses a similar initiating tension between modes (sacred) and major keys.

Example:

The tonality of "Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht" (Volksweise, 1807 catalogued by L. Erk) is Aeolian.

Because of the inner melody structure, the key could also be regarded as hypodorian (tenor on C)-equally. Only the "blunt', archaic malleability which radiates from the melody fine is important and it is just as important that ecclesiastic tunes are accepted in the original in jazz at the right geographic and historic place, namely Middle Europe. Until today it remains unexplained how modal key signature which moulded the basis of European musicality from the early Middle Ages until the 16th century, appeared in American jazz of the 50s as material for improvisation Neither the church sounds nor even the Indian Raga model can have been, because of historical reasons, direct sources for Coltrane and Miles Davis. And it also seems important to me that Gumpert uses model folk songs and does not enter into the equally available material of sacred music from the Middle Ages and Renaissance. The folk song in its short, concise almost thematic structure seems ideal for improvisation. Gumpert, however, prepares the Lied in the first place as a harmonic narrow closed theme in a major third. The improvisation (especially that of Klaus Richter, tp) can thus "open" it, while it contrasts Aeolian and A major, improvised and interwoven: a unique harmonic suspension, a static persistence comes into force as a basic musical mood.

Another example

is the original major tonality of "Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen". Conrad Bauer, tb, changes the key while improvising upon the fundamental harmonies and this causes the modulation. F major tonality contains in the song

![]()

is thus changed to C through a mixolydian postponement of the harmonies.

![]()

The tension between a firmly advancing major key (captured in the extended rhythm of the percussions) and a mixolydian "static" mode creates a spacious "swinging" suspension that is quite similar construction to the harmonic tension (space) of the Blues, surrounded by rhythmic stamping, but shows quite an individual expression.

And another example:

This Blues oriented spacious swinging suspension can also be directly engendered within the modal scale as Petrowsky shows in his style of improvisation on "Der Maie, der Maie" which has since become personally typical for him.

![]()

(Gumpert does not always use the folk song as a whole but often only those parts which are of most interest to these purposes as quasi themes!) Under the theme folk song we acquire the tension of the fifth, the seventh and the minor third. Clearly the relation to the Blues scale.

![]()

Petrowsky, however, does not take it linearly or melodically but rather in its spatial conception, cleans it out while improvising somewhat the interior architecture of the Blues, containing mixolydian tonal areas. He fills it which quick static structures which have the effect of stenographic saxophone shorthand dictated in haste.

Later recordings show that these improvisation structures are not by chance (compare, for example, the piece "Just for Fun" on the LP of the same name). Today the Petrowsky style on this space oriented improvisation figuration is almost recognizable once more. In much the same way, the "Echos von Karolinenhof" resounds a few years later in blaring Prussian fanfare.

In the clear C major chord tonality a "barb" of the Lydian mode tonality lies hidden, with the typical tritone C to F sharp known in the early Baroque era as diabolus in musica. That roguish pulling apart takes place then primarily at this interval.

This aesthetic interplay between historically different sound systems exists because of a contact between different music languages which corrodes customs of aesthetic behaviour. Within the Gumpert following this idea is continued on different recordings. In some, the folk song adaptations were reworked into even more sharply contoured settings. 1973: The Old Song, "Aus teutschen Landen" ("Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht"); 1974: Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil: " Mehr aus teutschen Landen'' ("Saß ein schneeweiß Vögelein" und "Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen"). In others what was at first a provisionary earnestness, later became an ever more serious parody force. Sommer's "Crocodile" theme which was used again and again between 1974 (Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil) and 1978 (N' Tango für Gitti) used as well that spatial effect caused by the crossing of modal and major keys. (All recorded examples except those of the folk songs, are noted aurally.)

By the way: He who wishes to interpret the number (Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil) in its undoubted ambiguity determines first its charm but then finds it secondly intentional and thirdly superfluous when one listens to the music for this is a sarcastic formulation of naive and collective amazement. This aesthetic interplay between a thinned out and newly structured sound space has its roots in history. They are (already) fully developed in the aesthetic experience of Eisler with whose music language Gumpert and Sommer (and perhaps Petrowsky, as well) have become, as it were, great. By the end of the twenties the great example of compositions from the GDR had already functionalized church music which lay historically dead, awaiting construction anew, following the major-minor cadence pattern. Widely dispersed music histories thus converged at a modern point of time. Eisler discovered a music language which was unequivocal in its ambiguity while at the same time popular with complex structure,sharp and aggressive.

Gumpert, when asked about constructive jumping off points, confirmed in general: "The first definitive work before me - and we've already dealt with it - was the suite "Aus teutschen Landen". It will certainly not remain alone. As well as this, I see areas from which jazz will enjoy further development such as from the works of Thelonious Monk, Cecil Taylor, the "Dutchmen" Willem Breuker and Misha Mengelberg and also naturally the contemporary composers of E-music; and we must not forget Hanns Eisler." 7)

To state it in other terms, all these: folk song, Bebop and Free Jazz, parody and naive comedy, a touch of the classics as well as social-aesthetic relations, come together with new reference, forming a new synthesis.

(A Short Observation)

While Gumpert joins Eisler in his concrete aesthetic experience, the occupation of western jazz musicians with Eisler produces results which are not less interesting, though they seem temporarily to be marginal symptoms of the avant-garde scene. Brötzmann, Van Hove and Bennink (however in only one single, FMP S 3) express their force and intense in an uncanny united front. The duo Heiner Goebbels and Alfred Harth - at least this is what I hear in their music - are obstinate about the Brecht/Eisler evaluation of subject matter. First with regard to Eisler pieces from the Weimar time itself and then extending the traditional, they improve and attempt to sample the emotional and historic thought force of past music and bring it to life in present day political experience. They have done this from Rameau to the Irish folk song; from Robert Schumann to the song from the Spanish Civil War.

Do east and west share any common ground? The culture-political GDR weekly magazine "Sonntag" has found the reason for a sharing. "These contacts (between western and eastern jazz musicians) are particularly interesting when considering that jazz in these countries is hardly integrated into the manipulated capitalistic entertainment industry and regards itself - at least with its most progressive representatives - as an alternative to commercialized music almost part of a second culture. Meetings with musicians and groups from the Federal Republic of Germany (Brötzmann, Mangelsdorff, Schlippenbach and others) from England and Holland were therefore very exciting for our development and promoted an understanding of ourselves through the function of jazz in our cultural scene." 8)

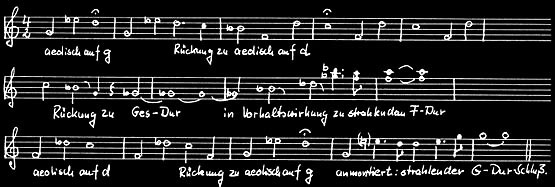

2. Rhythmic Ambiguity

Harmonic tensions between the Blues scale and the expansion of harmonic contents find themselves suitable in the rhythmic-meter area. There the feel of African music presents itself in western form. Words such as polyrhythmic, off-beat, swing, and timing are sufficient to outline what is meant.

A quite individual aesthetic of rhythm has developed out of the meeting between free improvisation and folk song in GDR jazz. It seems more raw, more difficult, more burdensome, is of a precise archaic naiveté and force, of which Günter Sommers percussion stands as exemplary.

The technical performance and improvisation which are associated with "Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen" show the folk song as a catalyst of rhythmic complexity and intensity such as this. Expressed in other words, when one hears Sommer drumming one knows whence Sommer's drums have come.

When the meter is in one, in three and in four: The result is a rhythmic metrical stratification within a given tempo which begins to swing (how can it be described otherwise?) and swing in a very German way, a very good way.

III Folk Song: Binding and Liberation

When the folk song is used on the one hand as a catalyst ton produce rhythmic-harmonic qualities it serves, as well, as the push-off point from the "safe shore" of aesthetic associations, over to a place of which Sommer said, "It is of increasing interest to me to assimilate and digest all my daily reality whether it be acoustic, individual or social as well as musical." An important piece which illustrates this has been mentioned before, the arrangement of "Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht" on the Old Song (1973) in which three phases are clearly differentiated.

After the introduction of the song (which was originally in the Aeolian mode) in the given major mode the piano and saxophone imitate (1st) each other in articulation. Gumpert repeats the theme of the prepared melody until it separates, loses connection, falls apart and becomes unrelatedly banal. The themes are suddenly reduced to the vigorous gesture of single tones. Structured form has become mere formula and seems preferred. There on, Hering (on saxophone) and Sommer develop an increasing intensity which, as it destroys, becomes more concentrated, stronger and faster. Here for the first time (at least documented for the first time) Sommer mounts the earthy, marching beat of the folk song, with a jazz playing style, with free flitting, meter less Hardbop configuration. At the high-point comes Sommer's obligatory out-cry. Almost as a re-statement of origins Sommer includes half of his drums and drums out the ending, as in reprise and thus holds fast to the polyrhythmic, strongly marked arrangement of "Tanz mir nicht mit meiner Jungfer Käthen". Here Sommer reaches out in the way that we have come to know.

Even though the song is played to death with moods of anger, naiveté, solemnity and authority, it cannot be killed. Maybe it is not meant to be.

After a short quiet playing of the minor third (3rd) which lies there like a Blues note, it is inadvertently stumbled over then pops back to its original position like a jack-in-the-box with a romantic conciliatory final chord.

"When something romantic flows in, it is more or less ironically treated. With Günter Sommer as duo partner, for example, irony represents a vehicle for us. We use quotations which mean “Merkt ihr nichts Leute “ 9) The folk song, which one year earlier in the original suite "Aus teutschen Landen" was still attempted with aesthetic connections, still stiff and somewhat dry, it set here at a distance and parodied. Not quite the folk song, itself, rather its ideological use as romantic adhesion for social, no longer supportable contradictions and as an exercise in Fascism for youth. Both functions seem to be interwoven; march gestures, fanfares, conciliatory piping in thirds and insipid bubbly end-chords critically denouncing upper-class perversion.

After a short phase, during which the GDR patterned itself after western chaotic Free Jazz ("even though not emanating from the level upheld by the social order there" 10)), the folk song becomes, at first, a stabiliser and catalyst for self-reliant harmonic-rhythmic improvisation and then by the mid-70s increasingly becomes an object of critical ideological robbery which, however, leaves plebeian substance alone. That which is musically rational is used more and more as a steering guide and that which bears on the folk characteristic, the trivial humour, is put into dry dock.

How is this possible? When I hear Gumpert and Sommer being played, I recall Prussia and Heinrich Heine, Kurt Tucholsky and the Weimar Republic. 1979 at the New Jazz Festival in Moers:

"Without doubt the high-point of the last day were the crazy jazz high-jinks of the Ernst-Ludwig Petrowsky Octet from the GDR (whose members were the same as those in the Ulrich Gumpert Band). With an ever more towering spirit, the pompous pretensions of solidified tradition are blown away, yielding to a hint of aging Prussia in the music of jazz annihilation. This pleasant jazz performance is contrary to the aesthetic bugbears and labels; contrary to hollow authority and exaggerated banality. The way into modern jazz is prepared here for the Schönberg/Eisler concept from the truth of musical thought. March and waltz are dissected and dispersed, their phraseology no longer of use; a sunrise of endless light in C major which, with a twist of hopeful irony, refuses to set and in reality is played as majestically as all musical sunrises and moments of enlightenment in the history of music." 11)

By the way these must have been the "Echos von Karolinenhof."

IV Parody and Alienation, Aesthetic Experience in GDR Jazz

Don't you get it, folks….

First Example (1973)

The phrase "Kommt ihr G'spielen" from a folk song arrangement in the suite, "Aus teutschen Landen" is neither modal nor shows any peculiarities of aesthetic intrigue which would be woven in through improvisation. The melody is in D major, bright, clear, with narrow cadence. It can hardly be varied and can only be reproduced. It remains unbroken, only a small detail is different. The tempo is barbaric, tightened. The bright D major reaches plain heroics, unbending lordliness. This is the point about which it seems to move, as if programmed: D major, two sharps, the king is dead, long live the king. The emotion of stored up ideology is thus thrashed out, in parody. The usual is made alien, the clog dissolves in singing; reality is referred to as experience and from. Brecht and Eisler named this aesthetic process, alienation:

"….alienation should only be allowed to take the stamp of confidence from the processes which have as social influence which protect it from attack even today. That which remains unchanged for a long time, seems unchangeable. At all events, we have a common meeting ground, that goes without saying and we must make an effort to understand it. That which is experienced with one another seems to be the human experience. The child, living in the world of the aged, learns what it is about. The way things are run will become familiar to him. In order for these to be made doubtful, he would have to develop that peculiar insight which the great Galileo had when he observed the chandelier which began to sway. The swaying astonished him. As he had not expected it, he could not understand it, but trough this he came to the concept of regularity. The theatre must meet the challenge of this insight, difficult thought productive through its portrayal of humans living together. It must take its audience surprised and this is brought about through an alienation of confidence."

(Bertolt Brecht) 12)

Music, too, and specifically freely improvised music can challenge this insight into bad and inaccurate habits by critizing music as a socially unreflected custom.

This is an extremely brisk social process, depending on the particular interpretation of the music.

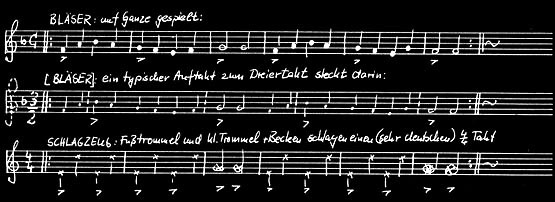

Second Example (1974)

"Wiesenlied", found in the "Old Song" right opposite "Es fiel ein Reif in der Frühlingsnacht" provides an example of horns playing in fifths and a fanfare with muffled chords, all in and around D major. Sommer adds to this, naturally, drums and stirring snare drums, the basic pattern of the German Prussian march which is used even today in shooting matches and military defence.

![]()

It is beaten and beated to death on flayed cymbals, until the tin drummer is exhausted.

Third Example (1974)

On "Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil" there is a "Take IV," preceded by a 22-second long "Petting zu 'Take IV' ". How does one pet musically? Onomatopoetically and bright, of course. In fanfare-like cadence upwards: C major/C-sharp major/D major.

What is the Prussian orgasm like?

Like a good German symphony, a consummate musical deed in the finale: ceremonial, in full chord, when possible in four-four time, and naturally in D major.

What is this damnable D major, anyway? Presumable a lump stuck in the throat of, and hindering real progress in German cultural tradition. In any case, it is the favourite key for bright, unburdened folk singing, a shining, optimistic glossing over.

Fourth Example (1978)

"…..jetzt geht's Kloß". A tonality is hacked to pieces. Above a rumbling bass trill, it strides downwards, d-d flat-c-b flat-b-a, in fourths. With vehemence, in D major, the world perishes (the old one, of course). Sommer drums his voom-voom-/voom voom voom - demolishing it with disdain and love at the same time. A bit of piano lesson is mounted like a commentary. Scales in contrary motion hang stupidly, amateurish and crookedly in the air to the accompaniment of a scraping, scrubbing drums. In closing, the fanfare pounds downwards, as with a first. And on the flip side, "Kloß II", what seems like untidy scribbles of school children at the blackboard become, in fact, a musical happening: a parody of noises- snoring; sawing; piano notes and knocking in an extremely high register; horns; echo effects; nothing - chaos wears away the last remands of contextual consistency.

"I have much more fun gauging a tone than listening to it. Phonometer in hand, I work happily and with assured ness.

Think of what I have already weighed and measured. All of Beethoven, all of Verdi, etc. That is quite a curious thing.

The first time that l made us a phonoscope, examined a middle-sized B. I assure you I have never seen anything of that kind as disagreeable. I called my servant in to show it to him.

On the tone weight-scale, a completely normal F sharp reaches a weight of 93 kilograms. It came, however, from a very fat tenor whom I had just weighed."

(Erik Satie) 13)

If the grand pianos of the GDR and the West Berlin Free Music Production are normally out of tune, then the dominant tone of the group surrounding Gumpert must be D; functioning as, D major chord, a dominant seventh chord (D7) and as a dominant the smooth, fine and soothing G major:

"Gumpert improvises while he composes, in the original meaning of the world. He puts together memories, naive themes, aphorisms from tradition, folk song intonations, even a simple progression of fifths is enough for him. In the encore 10 minutes of improvising are necessary for him to reach the dominant 7th chord. Gumpert repeats the established ostinato, over and over again, adding a little tone spice to it, cooking it a little, thus his musical substance can be heard. He turns it around and over, pulls it high, pounds on it and files it down. Throughout there are stops and pauses, unpredictable effects, even satirical effects come forth. A grateful oscillation between hard improvisation and buffoonery; something grotesque but with a light touch." 14)

The encore can be heard in the enclosed cassette, as the third piece (by the Gumpert-Sommer-Duo). Actually it brings forth the D7 in its drained and fragile Romantic form, even with the minor ninth, the essence of which is exaggerated, highly private feelings which must withdraw from reality. (With Eisler there is a similar composition-ideological occurrence in his choir piece Opus 13 from 1928 where social-democratic Bieder choirmen let the church bells swing in a dominant chord with a minor ninth.)

Naturally, these proceedings have, as well, much to do with Mengelberg. Bennink, Breuker and are inspired by the Dutch jazz fool scene.

They are only the intellectual "foster" fathers. Gumpert and Sommer create their own styles; the damnable D major; solemn tremolo; scales; piano lesson; hesitancy to grow up, the experiment, a testing of innate social-psychic stability in the reconstruction of a simple chord which bears, as well, within it, destructive power, incompleteness yet developing, shockingly and ironically recognized. It all seems to belong to the intermixing of musical clumsiness which circles about the laws of social-physical and psychic facility.

"I find it nonsense to play music with our backs turned to people. Why can't there be somewhere, a handle to grab hold of? (…) No one can even make anything of it with our music, not unless he himself has already made a beginning." 15)

In other words' "Jazz should not make humour its last possible expression. This is, however, not to say that every element of comedy should be taken humorously." 16)

What has to be demonstrated.

Tango, March and Waltz

The Frenchman, Satie, who had more fun measuring a tone than listening to it, made his eccentric and provocative way through the rigid aesthetics of middle class music at the beginning of the century. He promoted and practised the idea of music as furnishings, la musique d'ameuble, as an alternative to the awareness of Judgement Day hopelessness.

Music for listening, institution music, these already obsessed the citizenry after they prepared themselves to move from their erstwhile third place position to first place in the political-economic arena. During the19th century the citizenry put the folk song carelessly aside (or stylized it into the art song for pleasant listening) and created a new entertainment: the waltz and (and later on) tango for private use and the march and symphony for public use.

In jazz such development occurred and still occurs. Music characterizing the people is, as well, the music of the minorities. In its freest moods, it is the least avant-garde and caustic; at least with regard to the aesthetically muffled technologies which dominate the new music. Should jazz leave its attachments to the minority, it would experience a loss in business. Should it begin "to swing" for the masses it would then become "folksy". The more popular it would become, the less it would have to say through its style and form, thus becoming suited to the voiceless, powerless masses. Swing, brother, swing.

"It is worth noting that after a new form of music has successfully asserted itself there follows a levelling and lowering of market value. This could be observed in the swing era and in the era of Cool Jazz. These dangerous tendencies occurred even as a consequence of Free Jazz, and l would describe them as aestheticisms. By this I mean that music accounts for itself, through itself alone and not with regard to its relationship with society." 17)

To cull meaning from Eisler: "The concept 'stupidity in music' should be removed from the idea of general social stupidity (...).

"When human thinking lags behind historical time and behind social development, this I regard as stupid. (...)

It is astonishing to note the rise of stupidities in music, for human society has already liquidated its varying social classes.

But in music they still exist.

It goes without saying that no financier has feelings and thoughts such as those found in music.

This happens because music if furthest separated from the world of practical things (….). It is precisely because of this distance from the practical world, that music is muffled and archaic.

In a sense it is the incubator of stupidity." 18)

Even in the GDR the musical idioms which transport stupidity cannot, seemingly, be expurgated. Eisler has been honoured but not all of his opinions have become opinions carried through the media.

Before anything can be parodied, it must be portrayed. Once Strawinsky prepared small sketches from ragtime, tango and the waltz and march before commonplace art freed itself by alienations from the lofty demands of art. What is a tango? Petrowsky, Bauer, Koch, Winkler, almost all of those with dance music experience tried in 1973 (Just for fun) to characterize the essentials in a brittle sketch with typical rhythm model and tight melody phrasing.

But then:

The march: "Wiesenlied" on "The Old Song", "Take lV auf Krokodil"; "Marsch, marsch" on "N'Tango für Gitti (here with all the fixings, even a trio); Piece Number 4 (piccolo March ) to be heard on the next disc by the Friedhelm Schönfeld Trio.

The Waltz: "Aus Baby's Wunderhorn" and “Jubilee Suite" on N'Tango für Gitti; "Hahnenkopf" on Echos von Karolinenhof.

The Tango: "Kloß 1" on …jetzt geht's Kloß; on "N'Tango für Gitti" on the LP of the same name.

Swing/Bebop: "Königskindisch" and "Jubilee Suite" on N'Tango für Gitti; "Blau Blusen Blues'' on Echos von Karolinenhof.

These cannot be regarded as all inclusive, but rather representative.

"It is the damnable Proteus-like character of music that invites one to idiocy.

You need only to turn on your radio at any hour of the day, in order to hear an abundance of stupidity which you are able to recognize as stupidity even though you may not be a music connoisseur. There is a certain shabby vivacity, mostly, in waltz form, which is expressed in music. This is a kind of pseudo-military pretentiousness which is expressed in march rhythm.

There is a kind of melancholic pomposity, as Brecht always said: 'The so called significant symphonic works are like a man unable to digest a dumpling, or like colic'.

It all no longer has a real function."

(Hanns Eisler) 19)

Model of Form

The quoted material, the known gestures of tangos, waltzes, marches and swing never remain pure. Above all there is of course, the aesthetic pleasure, a slanting of the usual musical turns, an exaggeration, decorating them, disrobing them of their ideological substance, a dismounting, just for fun. A cheap pleasure would remain, if it did not consider or make musical comment. Three kinds of treatment can be heard:

For example "Kloß 1" on "….jetzt geht's Kloß". Amid the improvisation of Free Jazz, a tango motif appears, as if one unconsciously happened to turn a radio knob. Here is a tango, a kind of music which has become voiceless and dead as a form of communication which is here dragged in like musical folly within tradition.

For example "Hahnenkopf" on "Echos von Karolinenhof." The quoted gesture (which is seldom original marches, waltzes, tangos, etc.) is used as a theme for improvisation.

It is not difficult to recognize the Ländler (slow country waltz) as social behaviour, here somewhat demonstrated, for it conveys stable folk harmony, the picturesque contemplation of the common ego and inward peace, harmonic thought which are fastened to the emphasized downbeat ("one"). Because of this and not because of the melodic structure of the themes, improvisation is ceased as if it were a concrete situation: A certain shabby vitality of blinding, glinting optimism crows forth and, haltingly, truths are screeched back. Cautiously the brass and woodwinds produce cackle and babble in every increasing struggle (music imitative of coagulation). Brutal crashing piano sounds break out. The brass instruments form harsh lines of sounds; the neck of fake contemplation is wrung; the country knows no peace. Eisler has a terse concluding rule which gives one a persistent reminder of this. There is one very typical kind of improvisation, which, by the way, I have (as formed in this way) only heard from GDR musicians. Had folk songs been of definite theme material, the assertions in the music, revealed through the trends, feelings and situations of the music's contents, would have been independent and concentrated as in a "fable". To realize and at the same time to interpret feelings and situations in social and private behaviour is to wear out that which is emotional. Thus, "Krisis eines Korkodils", "Zweisam" and "Auf der Elbe schwimmt ein rosa Krokodil" (on the LP of the same name) are three different arrangements, while being three different aspects of, about, under, against and in the "Krokodils".

For example, "Jubilee Suite "on "N'Tango für Gitti" swings and swings, making valid an inverted fulfilling of Berendt's prophesy of style in the GDR. The hang-over follows, standing as if on an artificial foot: A motif of E flat minor thirds, which mournfully falls and rises, is repeated in an endless monotone (exactly 20 times). Cratorical directness and poetic openness are mounted together. A dialectic explanation for in the GDR, too, the final note on history has not yet been written. Attaching a slow waltz is like euphemizing a euphemism. The meaning comes not from assimilated improvisation but rather from a concise montage of differing gestures.

In all three forms of expression, the material is utterly used up, its ideological function critically played, in Order to place Free Jazz in high esteem and to expose it publicly. This is no mere collage, no mere playing about or mass entertainment, on idiotic play with others, using the medium of jazz. Improvisation is not a free rambling of thought nor is composition merely premeditated musical thinking. As superior as GDR jazz is at having traditional material and prototypical musical language at its disposal, it is occupied with the formal and aesthetic measures of jazz so concentratedly that a stage of consolidation is reached in which parody of the old and aesthetic emancipation of the new, as it were, naturally proceed away from each other:

"….to me Free Jazz means a form of music-making which encompasses many elements, for example, excerpts or material from older styles played with today's experience. Thus I see a wide spectrum of possibilities from which one can serve oneself in order to make a statement. It is, for example, possible to sing without accentuating four-four time. One is then not sure where the "one" is, as we say. Yet the music swings. One can use a ballad in a conventional way- or and this seems to us more interesting - one can use it by simply giving a hint of it or analyzing it and thus achieving a new quality in the music. That can happen despite the experiences of this ballad and their value to the understanding of how jazz is played. And finally, one can create a cylinder of clamour, a pure joy over turbulence and now and then (stated simply) a fun-filled in.

Through multiple performance variations Free Jazz offers particularly favourable possibilities of expression in our time." 20)

Annotations

1 Bert Noglik and Heinz-Jürgen Lindner: Jazz im Gespräch, Berlin 1978, p. 46 (Gumpert)

2 Joachim Ernst Berendt: Ein Fenster aus Jazz, Frankfurt/M. 1978, p. 228-229

3 Quoted from Rolf Reichelt: Jazz in der DDR. In: Bulletin des Musikrats der Deutschen

Demokratischen

Republik Nr. 2, 1 979, p. 3

4 Martin Linzer: Festivals zwischen Ostsee und Erzgebirge. In: Neue Musikzeitung,

October/November

1978, p. 11

5 Noglik/Lindner, loc, cit., p. 52 (Gumpert)

6 ibid p. 47 (Gumpert)

7 ibid p. 50 (Gumpert)

8 Quoted from Rolf Reichelt, loc. cit., p. 5

9 Noglik/Lindner, loc. cit., p. 47 (Gumpert)

10 bid p. 117

11 Jürgen Engelhardt: Big Band, Bebop und Bildungsmusik, Das 8. Internationale Festival

New Jazz in

Moers. In: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Heft 4, 1979, p.395 and 396

12 Bertold Brecht Kleines Organon für das Teater, Gesammelte Werke Band 16,

Frankfurt/M 1973, p. 681 - 682

13 Erik Satie: Memoires d'un amnesique. In: Musikkonzepte 1

1: Erik Satie, publ. by Heinz/Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn, Edition Text und Kritik, p. 85

14 Jürgen Engelhardt: Musik, die nicht rostet, Eine Übersicht des DDR-Jazz in der

West-Berliner

Akademie der Künste. In: Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Heft 6, 1979, p. 666

15 Noglik/Lindner, loc. cit., p.182 (Sommer)

16 ibid p. 181 (Sommer)

17 ibid p. 53 (Gumpert)

18 Hans Bunge: Fragen Sie mehr über Brecht, Hanns Eisler im Gespräch. München 1972, p. 45

19 ibid p. 49

20 Noglik/Lindner, loc. cit., p. 1 25 (Petrowsky)

Translation: Ruth B. Williams